The War Years

THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918

Harwich During The War Years

From Resort to Fortress

The biggest, and the saddest, event of the past twenty-five years was the Great War, and of all the places in England, Harwich has perhaps the most vivid memories of those grim years.

When with dramatic suddenness war did come, Harwich and Dovercourt, filled with summer visitors, with all the pleasantness of summertime in full swing.

Came the news that officers, and men of the naval ships had been recalled from leave, that the “Special Service” Territorials had been ordered to man forts. Mobilisation, the declaration of war – on that fateful Bank Holiday of August 4, 1914 Harwich changed from a holiday resort to a war-time fortress.

The visitors left, the borough of Harwich was officially declared a fortress and stringent regulations were quickly put into force.

There was panic, started by people who should have know better, residents wanted to bury their valuables, many left for more inland sports. There was a spy fever, many innocent people suffered temporary arrest, carrier pigeons were reported having been sent up from Harwich- the wildest rumours spread rapidly.

There was in all truth danger of a German raid on Harwich Defences had little force with which to resist. Territorial gunners were manning the fort and a company of soldiers was sent from Colchester pending the arrival of the Essex Infantry Brigade (Territorials) who were in annual camp at Clacton and had suddenly to pack up their red tunics, which they were never to see again, and march to Harwich.

10th Essex Regiment

Arriving at Harwich they were put to the task of making trenches and redoubts, turning indignant people out of houses, requisitioning barbed wire. Outposts had to be posted and some of the first shots of the war were fired by these Territorials who mistook some cows for Germans!

Within a few days Harwich was a fortress in fact as well as name and trenches stretched from New Hall Farm on the south, past the Tollgate and through the golf course to the West of Parkeston.

The Declaration of war on 4th August 1914 was announced in style by the Harwich Town Crier. The next day at 6 a.m. the people of Harwich lined the quays and seashores to watch the entire Harwich Force steam out to sea. Harwich was of great importance during the Great War of 1914-1918. Here was based commodore Tyrwhitt’s famous Harwich force which carried out many raids on the German and Belgian coasts.

Prince Lichnowsky

The German ambassador Prince Lichnowsky Arrived with his staff by special train from London to Parkeston quay for their return to Germany Aboard “St Petersburg” to Hook of Holland. When Prince Lichnowsky took over as ambassador to London in the Fall of 1912, he was given a difficult task, but was not expected to accomplish it. It was his responsibility to repair damaged relations between Great Britain and Germany He excelled at this job. Between the time of his appointment on 1912 and his departure in 1914 the Prince negotiated a colonial treaty, secured the peace of Europe in the 1912 Conference of Ambassadors, and brought about better feelings between Great Britain and Germany.

His success made his superiors in Berlin distrustful of him and his close relationship with the British foreign office. In July 1914, Lichnowsky pleaded with Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Gottlieb von Jagow, to use discretion in their support of Austria. In his view, Britain would definitely support Russia and France in a war defending Serbia against Austrian aggression. The Chancellor and the Secretary did not trust Prince Lichnowsky’s judgment because they believed him to be easily duped by the British. After the war started, Lichnowsky returned to Germany and spent the rest of his life trying to justify his actions

Harwich as a Naval Base

With the outbreak of World War I, Harwich became an important naval base, being closer to Germany than any other suitable harbour; A “Harwich Force” was established, under the command of Commodore (later Rear Admiral) Sir Reginald Tyrwhitt throughout the war. Harwich became the base for the 1st and 3rd Destroyer Flotillas and their attached light cruisers, as well as for the 8th overseas flotilla of submarines.

In Harwich itself, the Quay and steamers were taken over by the Admiralty and the Great Eastern Hotel were converted into hospitals.

The Harwich Force consisted of between four and eight light cruisers, several flotilla leaders and usually between 30 and 40 destroyers, with numbers fluctuating throughout the war, and organized into flotilla’s. Also stationed at Harwich was a submarine force under Commodore Roger Keyes. In early 1917, the Harwich Force consisted of eight light cruisers, two flotilla leaders and 45 destroyers. By the end of the year, there were nine light cruisers, four flotilla leaders and 24 destroyers.

Harwich Force

The combination of light, fast ships was intended to provide effective scouting and reconnaissance, whilst still being able to engage German light forces, and to frustrate attempts at mine laying in the Channel.

It was intended that the Harwich Force would operate when possible in conjunction with the Dover Patrol, and the Admiralty intended that the Harwich force would also be able to support the Grand Fleet if it moved into the area. Tyrwhitt was also expected to carry out reconnaissance of German naval activities in the southern parts of the North Sea, and to escort ships sailing between the Thames and Holland.

After the war, the Harwich Force became known as the Harwich Detachment, which consisted of a number of Home Fleet light cruisers and destroyers.

The Role Of Local Hospitals

At the outbreak of WW1, several places in Harwich were taken over by the Admiralty and for the Admiralty. Harwich was a fortress town so patients were not sent directly to this hospital – they would be transferred from surrounding camps and other towns.

During the First World War, the Great Eastern Hotel and its annexe was requisitioned on the 6th august becoming known as the Garrison military hospital. The Red Cross nurses under Mrs Brooks (wife of the local Jp) and men of the Harwich Volunteer Aid Detachment (under Commandant Etherden) hastily prepared the Hotel for the reception of the wounded brought back from the Western Front. The men also provided the Armed Guard for the first few months, until they were replaced by the Home Hospitals Reserve.

Great Eastern Hotel

The more seriously Injured servicemen were taken straight to Shotley for treatment. the Hotel furniture was replaced with hospital beds; Harwich was a fortress town so patients were not sent directly to this hospital they would be transferred from surrounding camps and other towns. Local residents would entertain the patients by providing concerts.

The Grange. Built as private house in 1911 for Mr Hepworth, was one of the many building taken over by the Government during the First World War as hospital or convalescent facilities. Here a group of nurses are leaving the front entrance of the Grange. concerts seem to be part of convalescence process and the men who spent Christmas 1914 in the GER Hotel were entertained by the nurse’s concert on Christmas Eve, and on Christmas Day were allowed to invite one guest each for tea.

Nurses at the Grange

The Grange was owned by Miss Lilley in the 1920s and was purchased by the council in 1939 for £5000, with part of the land used for a new fire station.

Red Cross Nurses on Parade at Harwich Town Station

In no former war have the Red Cross arrangements for succour, transport, and nursing of the wounded been so scientific a triumph of organization. The public showed itself eager to assist in the work. On all hands wealthy Britons placed their yachts and private houses at the disposal of the medical authorities. Our illustration shows a parade of trained nurses at Harwich.

Information courtesy/copyright of Heather A. Johnson. (Photo, Central News)

During the First World War, the Isolation Hospital was also used to care for soldiers and sailors with infectious diseases. There were four permanent nurses and, when more help was required, Red Cross nurses from the local Voluntary Auxiliary Detachment and nurses from the Ipswich Nurses’ Home were also used. After the war, the number of patients cared for declined.

Apart from the infectious diseases of child-hood there had been no major outbreak for many years and, due to its lack of up-to-date equipment, it was decided to close the hospital in 1938.

The admiralty requisitioned much of the Harwich .G.E.R fleet during late 1914, cargo steamers Clacton and Newmarket where converted to minelayers and minesweepers, whilst Munich and St. Petersburg were converted into hospital ships.

At Sea from December 1914 men were withdrawn from the light ships, buoys were left unlit and fog signals discontinued.

On the 12th of August 1915 a bomb was dropped by a Zeppelin which landed on Tyler Street, Parkeston, 19 people were injured; they were taken to Parkeston School for first aid treatment before some were transferred to hospital. Mr Crooks was at home at 17 Tyler-street when Zeppelins raided the port. “I woke up and found the sky above me,” he recalls. He received some minor injuries in the raid, and in the Second World War had his home bombed while he was living at Gidea Park.

Air Raid Damage 1915

Lord Claud Hamilton,P.C. (High Steward of Harwich), presented the St. John war service badges to ten members of the G.E.R. St. John Ambulance Brigade, at Parkeston, on Saturday, In recognition of air-raid duty throughout the war. His lordship said he did not think that the Germans had such a knowledge of geography as they were credited with, as many times they endeavoured to destroy Harwich and Parkeston, which are the headquarters of the fleet, would have caused incalculable damage to our country.

Harwich did not see much enemy action although bombs were dropped in 1916 and 1917 but failed to explode, one bomb landed near to St Nicholas church which also failed to explode. It was made safe and the casing put on display inside the church. On the 17th January 1921 Parkeston railway club was formed, the sailors rest building was purchased For £1 .000 from the admiralty. Nearby grounds where laid out by the G.E.R for use by the Railway club known as Hamilton Park.

The sudden and unexpected armistice was announced on November 10, 1918 and was greeted With gun fire, rockets where ignited, and ships sounded their sirens whilst work in the town was suspended.

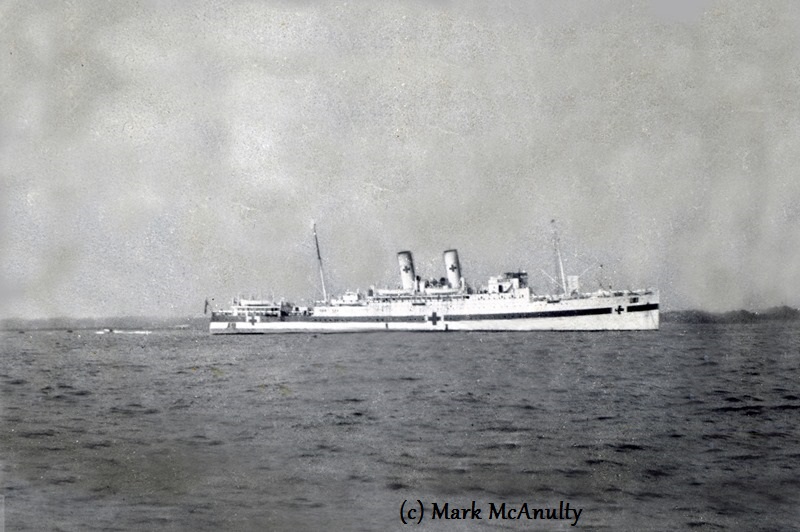

On the 10th November 1918 Airship R26 was spotted on the approach to Harwich harbour, Below where 20 German submarines 2 German hospital ships, all vessels were flying The white ensign. Over the next few months more German vessels surrended All under the control of Admiral Reginald Tyrwhitt.

On November the 11th came the signal ‘Flag General 1900, hostilities are to cease at 1130 and after the National Anthem has been played three cheers are to be given for His Majesty.’ But at 1130 the trawlers started their sirens and hooters and everyone joined in — the noise was terrific. In the evening the happy matelots were cheerfully obeying their Admiral’s order to splice the main brace at 2030.

When that longed-for hour arrived there was the most gorgeously spontaneous demonstration of joy that it has ever been my lot to see. All the ships switched on their lights and searchlights and blew their sirens. All up and down the harbour was a continual blaze of lights, rockets and coloured signals. As the night was a flat calm and clear, but very dark, the effect was beautiful.

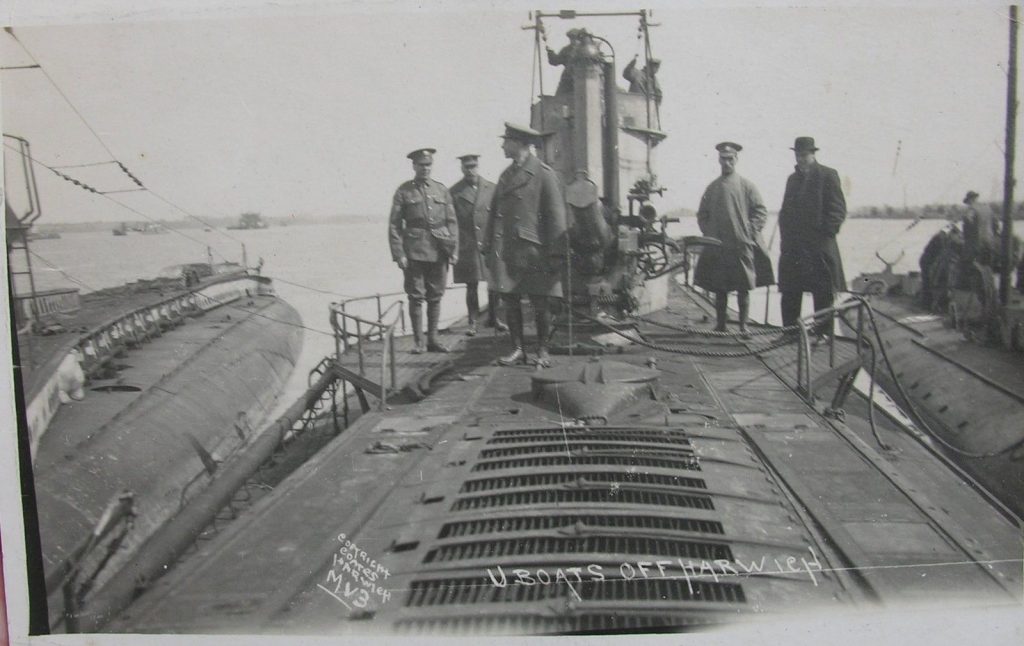

The first batch was to be surrendered on 20th November. Admiral Tyrwhitt had given orders that there were to be no demonstrations or taunting of the enemy, either by sailors under his command or by the people of Harwich. There was no such trouble; indeed, many people were concerned as to the mood and behaviour of the German crews, and there was particular concern about the possible booby-trapping of the craft.

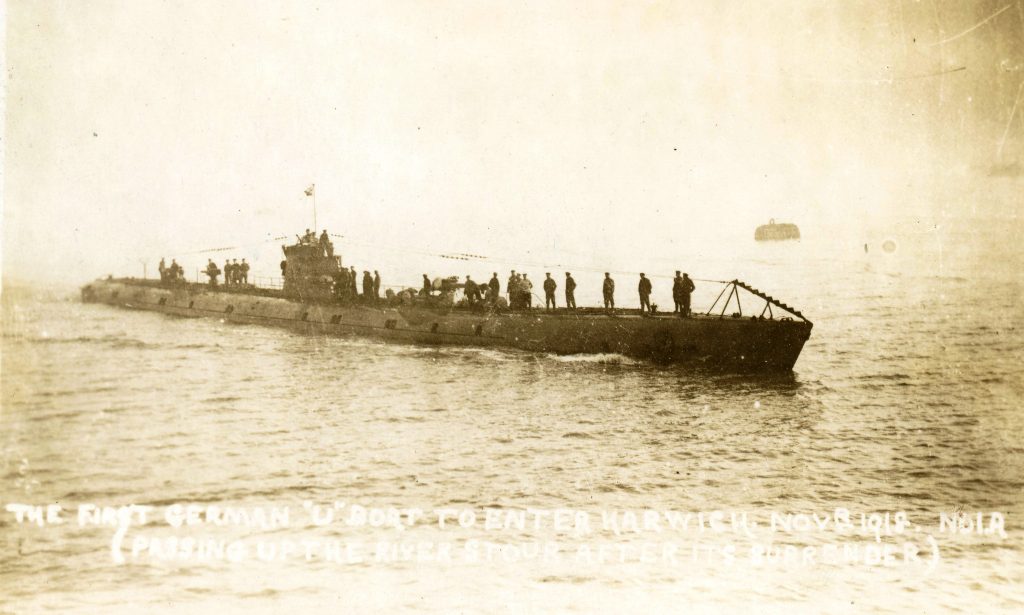

150 U-boats anchored in the river off Harwich.

The first units of the German Navy- in the shape of 20 first class submarines- surrended to Admiral Tyrwhitt in Harwich in December 1918. The morning was cold and frosty, and a thick fog lay over the harbour. Towards noon the sun broke through and crowds of people lined the shire to watch the scene.

First German U-boat to surrender.

The first signal that the U-boats were coming was the appearance of the British airship R26, and below her rode two German hospital ships, the Sierra Ventana and the Titania, with a British light cruiser in attendance. These two ships were to take back the surrendered crews of the submarines after they had anchored.

Then folowed the U-boats, each one flying the White Ensign, further batches of submarines and German floating docks and U-boat testers arrived to join what locals christened “U-Boat Avenue” during the following months, up to March, including ones that had been operating in the Mediterranean. The first batch of U-boats, along with a German transport ship, were lead into Harwich harbour. British crews had taken over command, and the Germans were assembled on deck. This first surrender comprised four divisions of five of the most modern type of U-boat. The German crews, having been as initially nervous as the British, took pleasure in describing the operation of their boats.

Once at Harwich the boats were moored in lines up the river Stour. The German crews were transferred to the transport ship for the voyage home. The Harwich Force magazine includes this account of the arrival of the first boats: Harwich was known as “U” Boat avenue with over 100 submarines laid in the harbour for more than three years. Over 27,000 German prisoners of war were repatriated from Harwich to their homeland on chartered vessels.

U-boat surrender

After some months, the submarines started to leave the harbour, having been sold. In March, seven of the larger submarines were sold to a Middlesbrough company, and 25 to a London company, with the condition that they had to be broken up and sold for scrap, one batch of four on tow for the Swansea breakers yard met an inglorious end; they broke the tow during a storm of Falmouth and drifted up on the beach to lay there for many a year.

The Dovercourt Minesweepers Memorial was unveiled at the junction of Fronks Road and Marine Parade on December 20th 1919. the memorial was unveiled by Adrmiral Cecil Hickey who released the large flags which covered the memorial.

Minesweepers Memorial

There was a large attendance despite the unsettled weather to watch the procession consisring of local clergy. the Mayor and Corporation. sailor boys from the Royal Navy Barracks and representatives of the Armed Forces.

The memorial itself is made of Portland stone with 4 tablets in cast bronze and 4 bronze dolphins, one at each corner. The dedication reads:

“To the Glory of God and in proud memory of the officers and men of the Royal Naval Reserve & Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve serving in the Auxiliary Patrol & Minesweepers at Harwich who died in the performance of their duties that the sea might be made free Twilight and evening bell, and after that the dark! and may there be no sadness of farewell. When I embark; for tho’ from out our Bourne of time and place the flood may bear me far. I hope to see my Pilot face to face, when I have crossed the bar.”

From 1919 the naval forces began leaving their harbour base. The Harwich Force was replaced by a Harwich Detachment consisting of light cruisers, destroyers and submarines and minesweepers.

The brother officers and men of the Harwich Auxiliary Patrol & Minesweepers subscribed to erect this memorial in remembrance of their comrades who gave their lives in the service of their King and Country during the Great War 1914-1919.

Kindertransport 1938-1940

The Kindertransport was a rescue mission that took place during the nine months prior to the outbreak of the Second World War. The United Kingdom took in nearly 10,000 predominantly Jewish children from Nazi Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Free City of Danzig.

The children were placed in British foster homes, hostels, schools and farms. Often they were the only members of their families who survived the Holocaust.

The principal ferry route was from the Hook of Holland to Harwich Parkeston Quay and the first ferries with the Kindertransport children reached Harwich, December 2, 1938; each group was about 200 children. After the children’s transports arrived in Harwich, those children with sponsors went to London to meet their foster families. Those children without sponsors were housed in Warner’s Holiday at Dovercourt Bay and in other facilities until individual families agreed to care for them or until hostels could be organized to care for larger groups of children.

Refugees Arriving At Parkeston Quay

Many organizations and individuals participated in the rescue operation. Inside Britain, the Movement for the Care of Children from Germany coordinated many of the rescue efforts. Jews, Quakers, and Christians of many denominations worked together to bring refugee children to Britain. About half of the children lived with foster families. The others stayed in hostels, schools, or on farms throughout Great Britain.

The last Kindertransport group left Germany (September 1), the day the Wehrmacht invaded Poland. This ended most of the Kindertransports. There was, however, one last group. A ship managed to make it out of the Netherlands (May 14, 1940). This was the day that the Dutch army surrendered to NAZI Germany.

At the end of the war, there were great difficulties in Britain as children from the Kindertransport tried to reunite with their families. Agencies were flooded with claims of children seeking to find their parents, or any surviving member of their family. Some of the children were able to reunite with their families, often travelling to far off countries in order to do so. Other times, they were not so lucky and discovered that their parents had not survived the war. In her novel about the Kindertransport titled The Children of Willesden Lane, Mona Golabek describes how often the children who had no families left were forced to leave the homes that they had gained during the war in boarding houses in order to make room for younger children flooding the country.

Dovercourt Holiday Camp

It is hard to convey in words the distress of parents forced to send their children away as the only means of saving their lives, or that of children separated from their parents. All too often, a brief farewell at a railway station was the last memory that the children would have of parents who stayed behind. The Nazi authorities, with characteristic callousness, decreed that the leave-taking must not be ostentatious, claiming that visible public gatherings of Jews and displays of emotion would arouse the righteous wrath of the Aryan population; for that reason, transports often left by night, sometimes from outlying stations.

While some children saw the journey as an adventure into new territory, the majority were frightened and deeply distressed. Common to almost all their accounts of the journey are their overwhelming sense of relief on crossing the border to Holland and their gratitude for the warm welcome they enjoyed there, in contrast to the treatment they had endured in Germany.

Life was not always easy, especially in the early weeks and months. Most children spoke little or no English. Throughout the war years the children worried about the families they had left behind, wondering whether they would ever see them again. In most cases their worst fears proved to be well-founded: all family members had perished. Not all the children felt comfortable in foster care, and in some cases, well-meaning but unsuitable couples became foster parents to the young refugee children. Those children who went to work often found life very hard.

By the time the Second World War erupted in September 1939, nearly 10,000 Jewish children had been brought to Britain.

The inhumanity and degradation that they escaped is immeasurable; the successful rescue operation in which so many participated was nothing short of spectacular.

On Sunday 25th June 1989, in the presence of the Mayor and Mayoress of Harwich, a hundred Jews held a reunion in Warner’s Holiday Camp. It was a nostalgic return to their first British home after arriving in Harwich as child refugees in 1938 and 1939. The 50th anniversary reunion was organized by Mrs Bertha Leverton, one of the original refugees.

In 1938, John Elliott purchased Cliff Hall and renamed it ‘The Elco’ and opened it as a private hotel and café. The declaration of WWII led to the business closing and it was soon requisitioned by the military. The building was subject to an incendiary attack in 1940, which set the roof on fire and resulted in considerable damage to the second storey. It was repaired and then became briefly under naval control mainly being used for, the women’s royal naval service.

The Elco

‘The Elco’ reopened briefly after WWII as holiday flats but did not prove very successful and the building was demolished during the summer of 1972 – it is now the site of Wimborne house.

THE SECOND WORLD WAR 1939 -1945

September 1939, the country heard the words of Mr. Neville Chamberlain – ” This country is at war with Germany.”

Small boats at Harwich Quay rolled and curtsied under a deep blue sky unsullied by cloud. Sun drenched riplets danced on the water and broke lazily, too small to splash. It was so deceivingly peaceful. Nations were preparing to tear each other to pieces but nature, with sublime indifference, shed her loveliness under a sky that radiated peace and affection.

The summer had rolled ominously towards war. Fear or inspiration, according to the people’s apprehension of coming events, had soaked into their daily lives. There was smell of approaching disaster. The older folk of Harwich recalled the previous war and the brief period of prosperity it had brought. They also recalled the humiliations and indignities of the poverty that followed in its wake. The gaunt and hungry faces at the door of the Bathside soup kitchen were still in their minds, vivid and clear. with victory came neglect, and roads and houses sank, and were still sinking, into an advanced state of decay.

Unfamiliar sights and sounds were disturbing their normal tranquil lives. Barrage balloons, moored on Harwich Green, hung ponderously over the town and the taut wires sang and sighed in the breezes to keep them awake at night. Long fingers of searchlights beat out the stars as they felt there was across clear skies and their trigonometrical patterns were mirrored in the calm seas of that glorious summer.

The harbour became once more an important but vulnerable base with its minesweepers, submarines and destroyers. The menace of Mines caused Harwich many alerts-the enemy frequently came in close to drop these deadly weapons.

With the approach of that memorable ‘D’ Day, more than 300 ships we’re assembled here for invasion of the continent.

Harwich, like all other towns, rejoiced in the turning of the tide and residents had a grandstand view of our planes roaring over to pound the enemy.

The borough if Harwich had 1,200 air raid alerts and no less than 1,750 Bombs were dropped. The borough was indeed most fortunate in being almost completely surrounded by the sea, for it was in sea that a large number of bombs fell and thus the casualties were comparatively slight Compared with the number of bombs dropped.

HMS Badger

The Second World War started on Sunday 3rd September 1939, and the RN moved straight into Parkeston the same day, taking over the quay and all the shore facilities, closing the area to all but Service staff.

Ten days later, a small London North Eastern Railway launch Epping, 22 tons, built in 1914, which had been hired by the RN four days before the war started, was renamed HMS Badger, and became for the next few months the nominal depot ship for the command of the Harwich area which covered Shoeburyness to Lowestoft. Due to the somewhat restricted accommodation the Navy looked elsewhere for a depot ship.

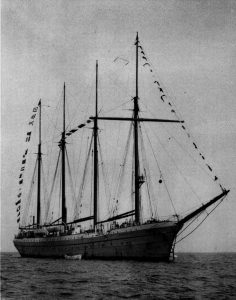

On 18th December 1939 the Royal Navy requisitioned an ex-schooner Westward, and on 12th January 1940 renamed her HMS Badger and released the little Epping for other duties.

HMS Badger

HMS Badger was a four masted schooner, 1680 GRT, built in 1920, and had accommodation for 80 people, with 12 bathrooms, 2 shops, bars, lounge and dining saloon. The new HMS Badger was to be at Parkeston for the next 6 years. Because of the scale of operations being carried out by the Harwich Destroyers, Submarines, Torpedo Boats, Minesweepers, Anti-submarine vessels and other craft, the Flag Officer in Command and his staff outgrew the comforts of the Badger, so they took over Hamilton House for the Operations Staff. At the same time, due to increased bombing of the area by the Luftwaffe, a start was made on excavating a small operations room in the hill behind Hamilton House, but problems arose and this was stopped in July 1940. It was nearly another year, March 1941, before work commenced on a large underground Ops. Room and Comcen under Hamilton House.

The combination of the ex-schooler Westward, Hamilton House, and its underground Ops Room, which made up HMS Badger served the country by its control of Naval and Merchant vessels in the southern North Sea during the remainder of the Second World War.

In June 1944, when the Allies landed in Europe, nearly 500 vessels were working from Harwich under Badger’s control. On 14th June 1945 the Operations Room below Hamilton House was closed down, and on 18th June Rear Admiral Burgess-Watson hauled down his flag and FOIC Harwich and his staff departed.

HMS Badger was paid off in October 1946 and renamed Westward and disposed of three years later. Her name was again changed to African Queen, and she traded between Italian port and Port Sudan. During one of these trips she caught fire, was towed into harbour, and scrapped. A sad end to a fine vessel.

HMS Badger was commissioned on 13 September 1939 as the headquarters of the Flag Officer In Charge, Harwich and was decommissioned on 21 October 1946, although the Operations Room remained as the Emergency Port Control for the Harwich area. The site was Parkeston Quay, now Harwich International Port, and the bunker lies under Hamilton House.

Hamilton House.

The Parkeston Quay site had been used during World War I by the Royal Navy, and an Admiralty Research Laboratory had been constructed there. The port was again requisitioned from the LNER at the beginning of World War II. In its early days Badger provided a base for minesweepers.

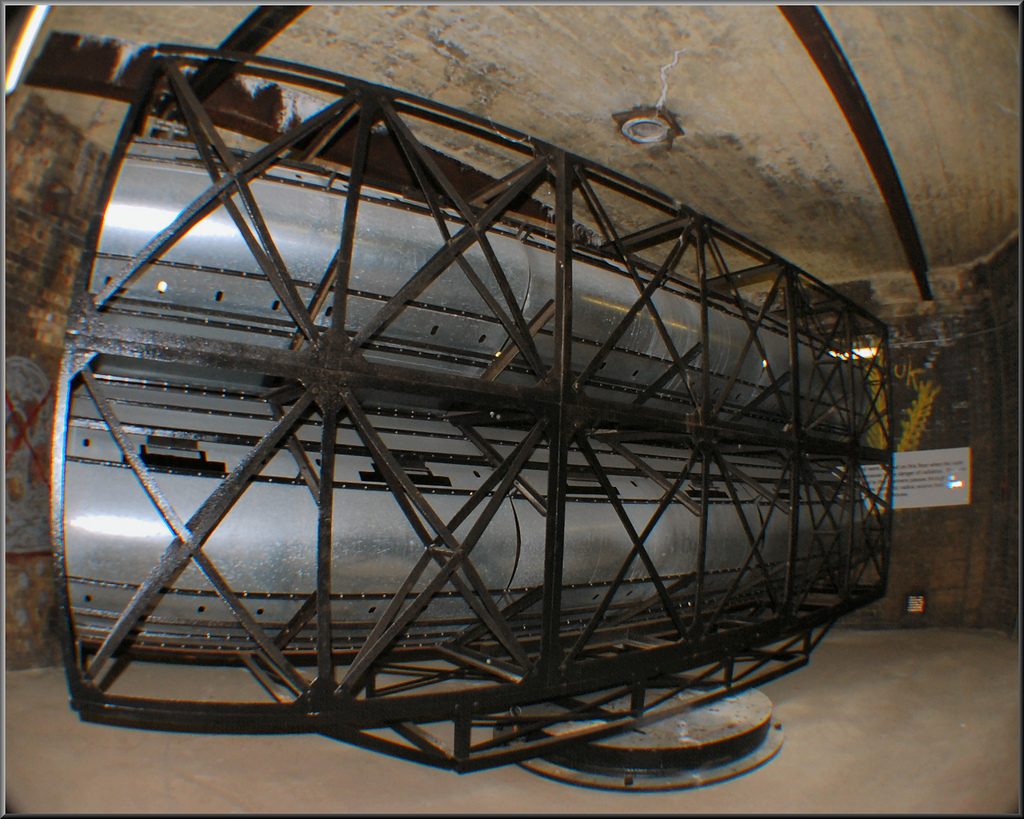

By the end of 1940 it also serviced a destroyer flotilla, a submarine squadron and a Coastal Forces Motor Torpedo Boat base, becoming the largest base for small craft in the United Kingdom. After a short period accommodated in the Station Hotel at Parkeston Quay, the accommodation and administration moved in 1940 to Hamilton House, the former Georgian customs house. A bunker was built under Hamilton House, and this opened in 1941 as an underground operations room.

Layout Plan.

The main entrance to the bunker is at the bottom of the basement stairs where there is a gas tight door with a small glass spy hole, beyond that is a second gas tight door forming an airlock. Between the two doors is a room on the right hand side which houses the boiler and standby generator. Through the second door the main corridor is to the right. The first room on the left was the RNXS office which is empty. The next room was the BT room this still retains a number of junction boxes on the wall. Next are the female and male toilets, both are identical with one WC cubicle, a shower and a wash basin.

On the right hand side the first room is the galley with a serving hatch into the adjacent canteen/rest room. The galley still has its sink and draining board, wooden units, food preparation table and a tiled wall. From the galley a door leads into the bar with a long counter and shelves behind where a till was located. The spacious rest room is empty. Beyond these rooms a corridor to the right leads to the emergency exit stairs. To the left of this corridor is the ‘communications centre’ consisting of two rooms. The inner room has a combination lock on the metal door with a notice, ‘This area is part of an electronically secure zone.

Operations Room.

© IWM (A 28937)

The main corridor turns left at the end with three small rooms on the left, each linked by a small message window. The first is ‘Staff Office Operation’ (SOO) and ‘Senior Officer Naval Control Service’ (SONCS). The next room is Head of Unit, i.e. the head of the RNXS unit based at Harwich and the final room is the ‘administration office’.

On the right hand side of this third corridor the first room is the large ‘Operations Room’ which has a small message window into the communications centre and large windows into the adjacent rooms on either side. On the right hand side of the operations room are two further rooms one has a wooden dais on the floor and this was the ‘seamen’ room, the second room has a large blackboard on one wall and was the ‘engineers’ room. The engineers are the mechanical and electrical engineers on a ship and the seamen are those who run a ship and take it to war. Both these rooms have a recessed escape hatch in the ceiling. On the left of the operations room is another large room, the same length as the operations room and half the width, this was the ‘boarding room’, new orders for ships would have been issued from here. Beyond the boarding room there is a short corridor to the stairs up to the main exit into the car park. The final room at the end of the third corridor is the ventilation and air handling room. This is another large room with the main ventilation plant and trunking along one side and the control cabinets on the opposite wall.

HMS Badger was decommissioned on 21 October 1946, but the operations room was retained. When the Royal Naval Auxiliary Service (RNXS) was formed in 1964 the bunker was refurbished and re-opened as the emergency port control for Parkeston, Harwich, the Port of Felixstowe, the Port of Ipswich and the River Orwell. Several of these centres around the United Kingdom were intended to direct shipping in the event of a nuclear attack. The RNXS bunker remained operational until 1992.

HMS Gipsy

H.M.S. Gipsy

HMS Gipsy was laid down by the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, at Govan, Scotland on 4 September 1934, launched on 7 November 1935 and completed on 22 February 1936. the ship cost £250,364. Aside from a brief period assigned to the 20th Destroyer Flotilla of the Home Fleet after her commissioning, Gipsy spent the pre-war period assigned to the 1st Destroyer Flotilla with the Mediterranean Fleet. She was refitted at Devonport Dockyard between 2 June and 30 July 1938.

On the outbreak of war in September 1939, Gipsy was deployed with the 1st Destroyer Flotilla for patrols and contraband control in the Eastern Mediterranean, based at Alexandria. Gipsy and her entire flotilla were transferred to the Western Approaches Command at Plymouth in October. On 12 November she collided with her sister ship, HMS Greyhound, enroute to Harwich, and her new assignment with the 22nd Destroyer Flotilla, but she was only slightly damaged. The ship rescued three German airmen outside of Harwich Harbour on 21 November and returned to port to turn them over the army. Later that evening, Gipsy set out with HMS Griffin, HMS Keith and HMS Boadicea to patrol in the North Sea. She struck a magnetic mine amidships outside of the Harbour, possibly laid by the aircraft whose crew she had rescued earlier that day, and sank. Thirty of her crew, including the captain, were killed. The 115 survivors were rescued by the other destroyers.

H.M.S. Gipsy

The ship’s wreck was upright on the seabed with only the bridge visible at high tide, but it blocked the channel. Only buckled plating amidships held the two main sections of the wreck together and they were cut by explosives when salvage began shortly after her sinking.

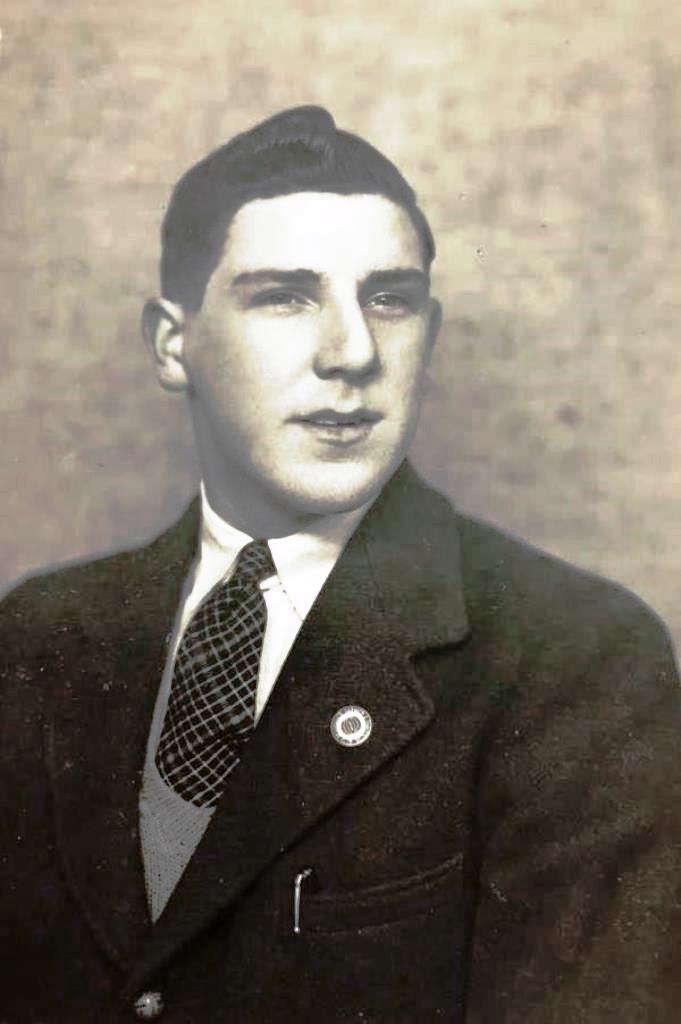

Lt-Cdr Nigel John Crossley was born in Bucklow, Cheshire on 29th May 1904.On the 3rd January 1939 he took command of the destroyer HMS Gipsy (H63).

Lt-Cdr Nigel Crossley

Nigel Crossley was seriously injured and also lost was his pet bull terrier Benjamin who always sailed with him and was by his side when Gipsy was mined.

Lt-Cdr Crossley along with other injured sailors was being treated in the sickbay of HMS Ganges. He was still in a coma and despite head surgery he died on Monday 27th November. He was 35.

He was buried two days later in the naval cemetery next to Shotley Church up the hill from HMS Ganges and overlooking the Harbour

Shotley Churchyard

The two halves were raised by pontoons, and were subsequently broken up. 30 of her crew were killed and the survivors were taken off by a Tug : Stronghold and the Polish Destroyer Burza. 750 long tons of ferrous scrap and 38 long tons of non-ferrous metals were recovered between June 1940 and February 1944.

Churchill’s anger over the incident led to Admiral Brownrigg being demoted for his inflexibility and the officer commanding coastal artillery for his negligence. An enquiry into the sinking of the Gipsy was opened on the 13th December at a hotel in Harwich questioning officers from the Gipsy as well as the other destroyers and other shore based officers. The enquiry took two days and its witnesses asked 157 questions.

The enquiry attached no blame to anyone, the only implied criticism coming in the recommendation “all units should have full information of the danger to be avoided.

On the 24th November 1939 the Chief Constructor of the Navy inspected the wreck. The next day temporary anchors were put in place to stop it shifting or disintegrating further. Sailors removed the foremast, guns, torpedo tubes and depth charges. At low tide on the 28th December local tugs secured the two halves of the wreck to giant floats so as when the tide rose the wreck cleared the bottom. The two halves were then towed up the channel and beached off RAF Felixstowe.

HMS Gipsy

An Admiralty inquiry was held afterwards, and, of course, all the local navy, army and RAF files were eventually opened at the National Archives.

They make it clear that the mine which sank Gipsy had not been dropped by the plane whose 3 survivors she had rescued earlier that day. In fact it had been dropped by one of two seaplanes which overflew the harbour entrance just before she left. The number of dead was 31, not 30, as her captain died in Shotley hospital a few days later.

The “good was requited with ill” thing comes from the newspapers of the time, who weren’t let it on the truth. Julian Foynes

There was some consideration given to re-joining the two halves but this was soon ruled out. In August 1940 the stern half was towed across the harbour and beached on Harwich Hard where it was broken up over the next few years. The bow section being close to the shipping channel was blown up in 1942.

- “Gipsy had never killed any Germans only saved some”

- relating to the three German airman she had rescued before sailing to her doom.

EVACUATION!

By late May 1940 Allied Armies were in full retreat across the Low Countries.

The historic evacuation of 340,000 British troops from the beaches of Dunkirk started on 29th May 1940. Invasion of Britain by German forces was thought to be imminent. The Minister of Home Security recommended the evacuation of all children from coastal towns of South Eastern England. Most of the parents and teachers of Harwich heard that advice on the radio on Sunday 26th May. It was followed by a week of intense activity, and on the following Sunday, 2nd June, two special trains took 1200 children and all teachers of Harwich, Dovercourt and Parkeston to new wartime homes in the safety of Gloucestershire and Herefordshire.

Evacuation 1940

The Government Evacuation Scheme was a voluntary affair and parents decided for themselves whether or not to dispatch their children. However, three quarters of the town’s children made the great trek west. For the quarter who were left behind in Harwich there were no schools, because all the schools had been closed after the departure of all the teachers. St George’s School was one of the schools taken over by the military. St Georges was used to control the barricade outside Main Road where passes had to be shown for anyone wanting to proceed further into town.

The schools remained closed for the rest of 1940, what a remarkable achievement it was that three quarters of the town’s children could be gathered up, transported A triumph of organisation.

During the Second World War hospital ships continued to serve the British Army in evacuating the wounded and injured back to Britain. Their number were supplemented by Hospital Carriers which had a shallow draught and could go close inshore to facilitate swifter evacuation of casualties. They were assisted by water ambulances with flat bottoms that could go ashore and carry stretchers.

Andy Rutter – Harwich Society

WHEN I WAS EVACUATED

When I was 8 years old my brothers David and Jack and I were evacuated as the Harwich area was deemed vulnerable from German invasion

In June 1940, our parents said goodbye at school, then we all went down to Dovercourt station to board trains to Thornbury and Ludlow.

My brother Jack, who was the eldest went on a separate train to David and I.

Stan Delves

After a long journey calling at Ipswich, Cambridge Yate and Thornbury stations David and I were assembled with all the other evacuees in Thornbury High School playground, and taken by car to Berkeley school in Gloucestershire Assembled in a line foster parents choose who they wanted to foster, David and I eventually were chosen and went to live in the Countess of Berkeley`s chauffeurs house adjacent to the castle.

All went well for a few weeks, swimming in the castle swimming pool. The countess all dressed in black favoured the evacuees to the local children and animosity broke out between evacuees and local kids.

All went well until my hot-tempered younger brother David through a dinner plate at our male foster parent. Alas we were split up. David going to the malthouse at Upper Morton, and me to different foster parents at Berkeley Heath, a mile away.

David in the meantime was looked after by the Harwich District nurse known to all the Harwich kids as “Nitty Nora” ,(Nurse Coran) because as the early part of the World War 2 nits in the hair was common, and she visited schools regularly from her clinic to examine children’s hair, and treat where necessary.

She was also evacuated to the Malthouse to look after several children not wanted by their respective foster parents.

After a few months, because of David missing me, I was reunited with him at Morton until coming back to Harwich in July 1941 after invasion threats had subsided.

Whilst in Thornbury we both went to the local elementary school; meals were packed lunches delivered daily by Nurse Coran on her bicycle.

Council School

Going to school each day we walked from Morton to Thornbury getting up to mischief as kids do. I remember the headmaster Mr Nicholls coming into our class and saying with tears in his eyes, that HMS Hood and been sunk A few days later, this time happy that the Bismark had gone down.

Whilst at the Malthouse we played football with a brand-new ball donated by Harwich & Parkeston FC had our own two rows of allotment, where we grew lettuce, parsnips & radishes, from seed bought in a shop in Thornbury. 2p a packet from our sent pocket money.

When at school, and the air raid siren went off, we were taken to underground dirty, damp shelters under the allotments, if a bomb had been dropped then I would not be writing my memories.

On Sundays we either went to Thornbury church or a small Methodist chapel down a lane near Morton, of course mucking about on the way to Thornbury. we never made it, so the vicar use to come to us and preach on the malthouse lawn.

Stan Delves 1931-2021

Hospital Carrier Amsterdam

The L.N.E.R. Ship s.s. Amsterdam was a regular passenger ship sailing from Harwich to the Hook of Holland, with nearly all the crew coming from Harwich and Lowestoft. During the Battle of the Falaise Pocket of Operation Overlord the Normandy Landings casualties were evacuated aboard the Hospital Carrier Amsterdam. She made several successful Channel crossings where soldiers were taken to English ports but sadly she struck a mine on the 7 August 1944. The engine room was destroyed along with about half of the craft and it started to list.

The QAs on board were up against the clock to get their patients below decks to the safety of the lifeboats. This quickly became dangerous and those patients who had lost lower limbs were helpless. The Sister in charge was Miss Dorothy Anyta Field of the QAIMNS and she bravely returned to the lower decks with fellow Sister Molly Evershed. Together they rescued 75 men even though the deck was angled to the surface of the water. Without a thought to their own safety they returned once more to rescue the wounded soldiers and sadly the Hospital Carrier Amsterdam sank taking the two QA Sisters with her.

Fifty-five wounded men were lost as were ten medical staff and thirty crewmembers. Also lost were eleven German prisoners of war. Total losses, 106 souls.

**Text by kind permission of The Queen Alexandra’s Royal Nursing Corps (ARANC).

The Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS)

WRVS (Dovercourt 1960’s)

Women’s Voluntary Services (WVS) 1938-1966; Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS) 1966-2004 and WRVS 2004- 2013) is a voluntary organisation concerned with helping people in need throughout England, Scotland and Wales. It was founded in 1938 by Stella Isaacs, Marchioness of Reading as a British women’s organisation to recruit women into the Air Raid Precautions(ARP) services to help in the event of War. The official story of the origins of the WVS say that Lady Reading was approached by Sir Samuel Hoare the Home Secretary who had telephoned her at Home asking her if she would start an organisation to recruit women into the Air Raid Precautions services. However, recent evidence has been found to suggest that it was actually Lady Reading who approached the Home Secretary. In a letter to Lady Reading sent after the end of the war Sir Wilfred Eady said “I think you know how proud I am to have been connected with the WVS, even though I was rather alarmed when you first brought the proposal to Sir Samuel Hoare.

Memoirs of WREN Sheila Bayley: 1939-41

Sheila Bayley

I was on the quay in Harwich one evening in 1940 (having done a 12-hour shift driving) and just going home by car when two chaps came up — a Lieutenant-Commander and a Lieutenant — and said “Where is the Admiral’s office? Could you take us there chum?” I said “I’m just going off duty.” They persuaded me to take them and I said, “All right, I’ll take you but I won’t bring you back — somebody else will have to bring you back.” So I took my future husband and his First Lieutenant up to the Admiral’s office. After that I learnt that the reason he asked to see the Admiral was because his ship, HMS Whitshed, had been blown up by a mine — the whole of the front was blown off it. I remember having to take a truck down with some Petty Officers to collect the remains of the people who were in the front of that ship when it was blown up and a Petty Officer saying “Don’t look, Miss, don’t look.” (It happened in January 1940, I think, when the Whitshed out of Harwich was blown up in the North Sea by a German mine.

The Lieutenant-Commander brought the ship in backwards because its bows were blown off, and he managed to seal the doors and pump out some of the water to save the rest of the crew. He got the DSO for this. This was described in a book, HMS Wideawake — the names being changed because of the War.)

Then after I left Harwich and went back just to see my friends, I was asked on board the Southdown, which was a corvette, because I knew the Captain, who had been to a dance with us when I lived at East Bergholt, because he was at Shotley then. The other guest there was Ré Conder, who had been the Captain. After the Whitshed, he had been given the Southdown, and was now handing it over, and he said, “I’m in London now. I’m a lonely man. Come up and see me sometime.” I’d no idea what he was talking about, although I understood that his wife had died. Anyway, I never got in touch with him — and lost a couple of years there. We didn’t meet again until I happened to go by chance to a dance on HMS Renown in Gibraltar during Operation Torch, but that’s another story.

I became an officer either late in 1941 or at the beginning of 1942. I had to go down to Greenwich to do an officer’s training. They tried to make us march, but we weren’t very good about doing that, and we had to sleep in the cellars every night on mattresses, because there were bombs, and I got scabies, of all the awful things to get. My father said the soldiers used to get it in the First World War.

Then I had to go and have an interview and they said, “Well, you cannot possibly go back to Harwich.” I burst into tears, not being very well, and said, “Why not?” They said, “Because it wouldn’t do. You’re now an officer. You would be with the Wrens.” I protested but it wasn’t any good and that was it. I was too ill to get home any other way and so I got a taxi all the way from Greenwich up to Hampstead, where my parents were then living, and recovered there. I went back to Harwich and saw my friends, but I couldn’t be a Wren there any longer.

Air Raids

Air Raid damage

During the Second World War Harwich escaped the real wrath of the German “Blitz”. The borough faced over 1100 ‘Red Alerts’. Only 100 less than Central London, yet on the great majority of these occasions the approaching enemy either stopped short and dropped mines at sea, or flew past for inland targets. For at least 400 planes in all, distributed in some 70 raids, exact figures cannot be given, because the relevant German records have not survived and much of the night bombing was too scattered for its exact objective to be known. Harwich Harbour and the towns alongside it were bombed just as much as other East Anglian naval bases. The fatalities in air attacks were 20 at Harwich & Dovercourt, 2 at Parkeston.

About thirty enemy aircraft were downed while raiding Harwich, but the strangest incident was on the night of the 20th of October 1940 when daylight revealed a undamaged Dornier 17 bomber which had embedded in the river mud at Parkeston. Exhaustive searches by troops and police for miles around revealed nothing of the crew. As far as local people were concerned, the mystery may never have been solved.

Harwich itself was hit on the longest day of the year, 21st December; the Italians got all their bombs into the Harbour area. One fell in the water off the Low Lighthouse, another on mud at Shotley, and another in fields near Dovercourt. The only bomb to do any harm demolished the International Stores in Kings Quay Street, wounding about thirty people in nearby houses and causing one man to lose his leg.

The Second World War thrust Harwich back into the limelight, but unlike the 1914-1918 war, civilians were in greater danger this time. This photo shows damage that bombs could cause. Tagg’s General Stores in Grafton Road seems to have suffered a direct hit at 8 minutes past 10 on the evening of February 25th 1941. Considerable structural damage has been caused, but the advertising boards for Cherry Blossom, Craven A and Lyons Cakes can be seen.

Five people were killed in this raid and houses were damaged in Park Road, Grafton Road, Main Road, and Beacon Hill Avenue.

Attacks continued throughout 1941 and there were frequent reports of structural damage and deaths. Una Road, Parkeston, was hit in April and a direct hit on No’s 18 and 20 Cliff Road caused major damage. There were fatalities and a female was rescued from the debris after a ten-hour search. Two days later, the volunteer workers found a female body in the debris. A new type of mine hit the Ordnance Buildings in Harwich on May 17th 1941. The building was absolutely devastated and two deaths were reported.

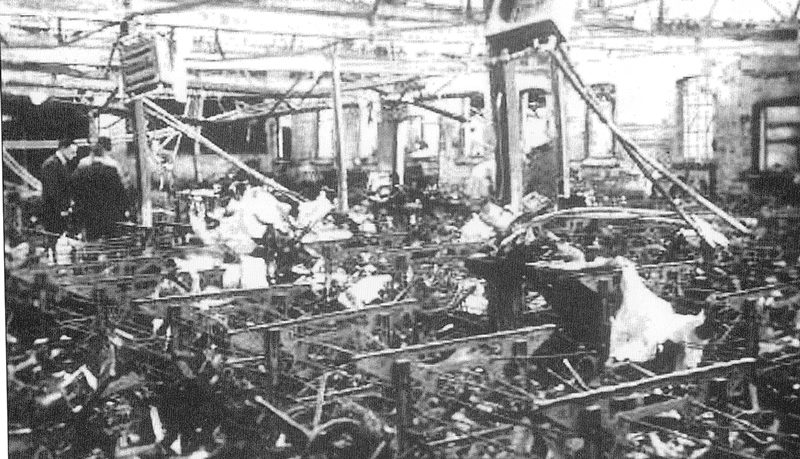

Bernards has always been, throughout the 20th century, a name synonymous with Harwich. Charles Bernard started tailoring naval uniforms in 1896. The threat of war in 1938 led to the whole production line concentrating on uniforms, and extensions to the factory were completed in 1940. A second factory was set up in Luton ‘just in case’. On May 9th 1941 a German bombing raid destroyed the factory and the aftermath can be seen here.

Production started again with three days in alternative premises and a new factory was rebuilt within five months – a not inconsiderable feat in the circumstances.

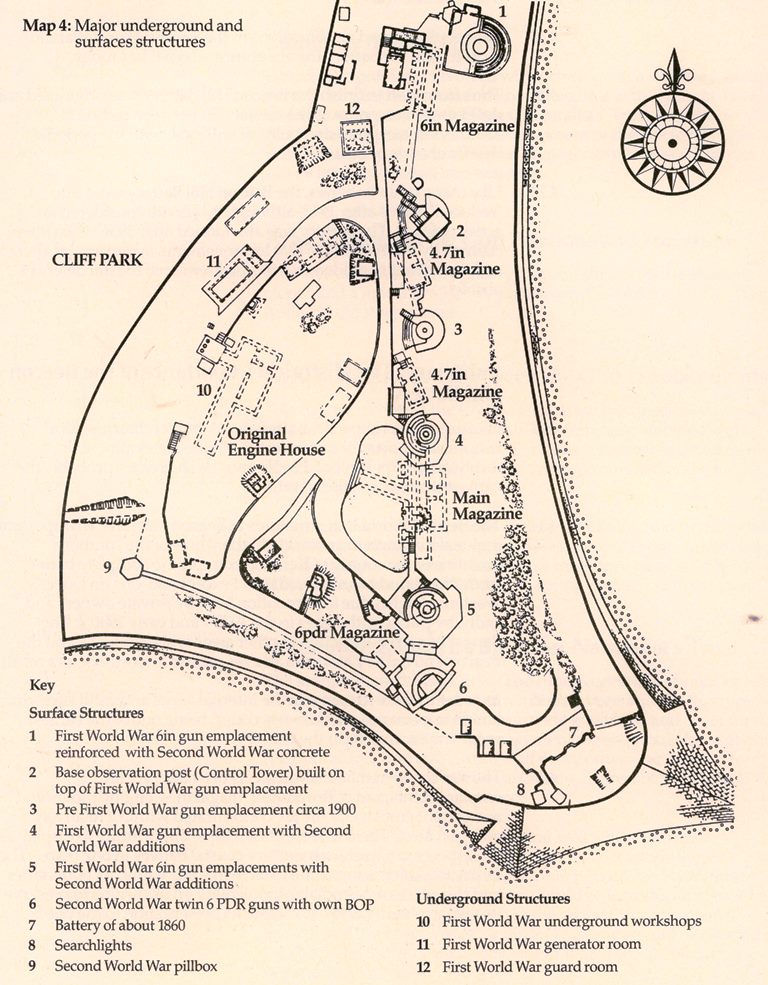

Beacon Hill Fort

Harwich was in the front line defences during WW1 and Beacon Hill Fort was once again improved With the further threat of war with Germany, plans were drawn up to reactivate and rearm the fort but it wasn’t until 1940 that any new works were started with the construction of the Cornwallis Battery which consisted of a twin 6-pounder emplacement with a rangefinder and predictor tower at the rear.

Beacon Hill Fort 1974

With the depletion of the German navy a seaborne attack was eventually considered unlikely but with the increased threat of an air attack by the Luftwaffe the air defences at the fort were improved with flat-roofed concrete casemates constructed over the two 6-inch Mark VII guns, there was also a Bofors anti-aircraft gun added to the roof of the southern emplacement. A battery observation tower was constructed on top of the abandoned 4.7-inch emplacement. In 1947 the 6-inch guns were removed from Beacon Hill but the twin 6-pounder was retained until 1956 when the fort was decommissioned and all the artillery was removed. The train ferry berth, continental pier and the halfpenny pier became the base for salvage vessels. Also stationed here was the 12th paddle minesweeper flotilla, which included paddle excursion vessels and rescue tugs. The former great eastern railway hotel became the administration office for these vessels and would Accommodate their crews.

Plan

Harwich Radar Tower

The Harwich Radio Direction Finding (RDF) Tower was built just before April 1941 and housed one of the earliest applications of RDF. Ten similar sites were built around the UK covering important rivers, docks and harbours. RDF became better known as RADAR around 1943, an American term short for Radio Detecting And Ranging.

It was used to cover the naval minefield that had been laid across the estuary between Essex and Suffolk. The range and bearing would be transmitted to one of the Extended Defence Officers (EXDO) posts at Beacon Hill or Landguard Fort, from which the appropriate mines were selected electrically and detonated.

Radar Tower

The ground floor of the tower consists of five rooms: The generator room, crew accommodation, mess room, Toilet and lobby (this includes a hatch to the middle and top floor, used to raise equipment). The original generator remains in situ.

The middle floor was the Operations Room. It would have housed the equipment needed to operate the array (aerial) on the upper floor. This would have included a transmitter, receiver and telephones etc. In the centre of this floor is the manual device used to rotate the array on the top floor. Two men would slowly swing the aerial back and forth across the minefield until the strongest signal was detected from an incoming vessel, this was the bearing. It was never used as a plotting room as this operation was carried out in the EXDO towers.

Harwich Radar

The top floor houses an extremely rare survivor, a Type 287 RDF array. This is largely original and consists of two ‘pig trough’ reflectors, one above the other, both 21 feet (6.4m) wide. It was powered by the generator on the bottom floor; this gave it a range of 2 miles, enough to cover the minefield. The Type 287 was a modification of the earlier Type 284 that had been used on battleships, including the HMS Hood, and was used for gun laying. The 50cm wavelength and 5 degree signal width made the types 284 and 287 ideal for pinpointing vessels at sea level.

Opening times to follow – for more information please contact harwich-tower@outlook.com

A War at Sea

From the outbreak of war the continental shipping services were suspended, the harbour was closed to passenger traffic, and all but 2 of the railway ship were requisitioned as transport ships. The Train ferries sailed between Harwich and Calais carrying guns and heavy equipment.

By 1940 HMS Badger were home to destroyers, frigates, corvettes, submarines, motor torpedo boats and other small service vessels. The Navy undertook repairs to motor launches and motor torpedo boats.

St Denis

Fearing a German invasion of the Netherlands St Denis and Malines were ordered to sail to Rotterdam on the 26th April 1940 to prepare for evacuation of British personnel. Amsterdam, Bruges and Vienna were sent to Le Havre on the 11th June 1940, whilst approaching Port they came under aerial attack. Bruges received two direct hits, and was beached near the harbour entrance. Vienna was able to get into Le Havre and rescue troops and the crew of the Bruges. Amsterdam successfully picked up 1,800 troops and became the last merchant ship to leave Le Havre.

Malines, Sherringham and Train ferry no 1 where used to prepare for evacuation of the Channel Islands in June 1940.

Train ferry No.1 and Train ferry No.3 now renamed H.M.S. Princess Iris and HMS Daffodil had a large gantry crane fitted to the sterns which would enable the discharge of heavy equipment at ports. Prague and Amsterdam were used as hospital ships. The crews of the former railway Boats came mainly from Harwich and many died when the Amsterdam was mined and sank.

The close connection between Harwich Town and its harbour has been remarked upon by many over the centuries. However there are times between 1940-1945 when Harwich was certainly saved by the sea, there were 1200 air raids and 1750 bombs were dropped – a large number fell in the sea making casualties slight.

Troopship Service (1945-1961)

The Trooping service between Harwich and Hook of Holland commenced in 1945, Parkeston Quay was used as a base for large British troop movements and the repatriation of civilians stationed in Germany as part of the occupation forces. The service lasted for sixteen years and was maintained by several troopships.

Waiting to board Empire Parkeston

There were three ships originally, the Vienna, the Empire Parkeston, and the Empire Wansbeck. Backwards and forwards they plodded with personnel serving in Germany.

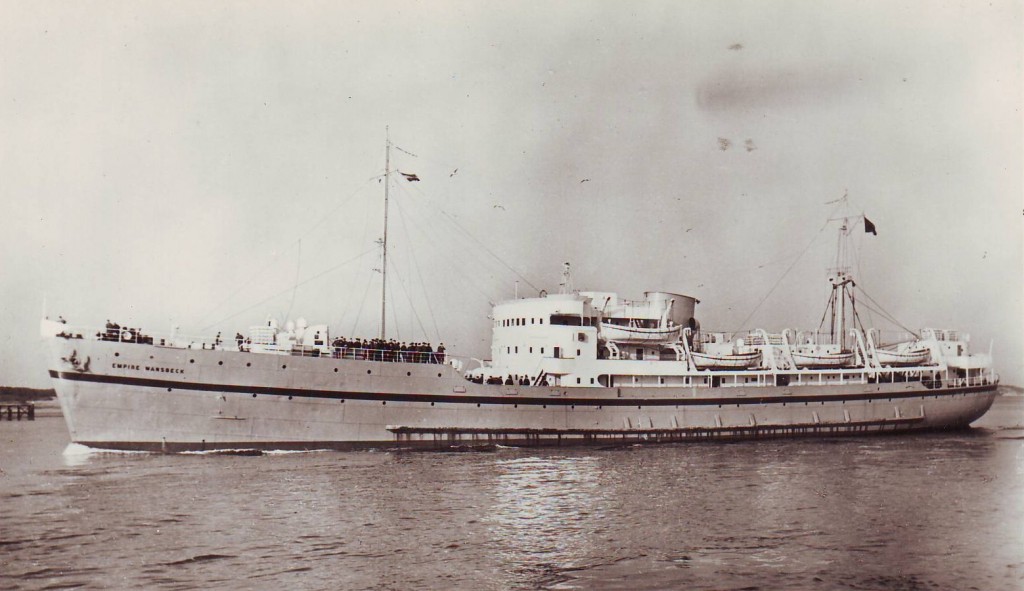

Empire Wansbeck

Empire Wansbeck (1945-1961) Built by Danziger Weft Ag,Danzig as a German minelayer Linz in 1943 .it was acquired by the M.O.T under the reparation scheme in 1945 ,she arrived two days later at Parkeston Quay to take up trooping movements to the Hook Of Holland. after completing 2,030 round voyages she arrived at Parkeston Quay for the last time on the 26th September 1961.

After a period of lay up Empire Wansbeck was sold for £85,000 in March 1962 to Greece to become a cruise ship, she was withdrawn from service in 1980 and eventually scrapped in 1981. surviving until 1978.

Vienna

(c) Alan Kitching

Vienna (1945-1960) Built 1921. Bought from the London and North Eastern Railway in 1941,Vienna became a hospital ship and troopship. during her post-war career Vienna experienced a number of accidents, 11th February 1952, Whilst berthed at Parkeston Quay ready for a 23.00 departure, an explosion in the starboard chamber of no 3 boiler occurred discharging the contents into the stakehold. on entry to the boiler room 5th Engineer C.Mckaig and Donkeyman M.Gunn were found to be dead.

s.s Vienna arrived at Parkeston Quay for the last time on 2nd July 1960,she left for the breakers yard in Ghent September that Year.

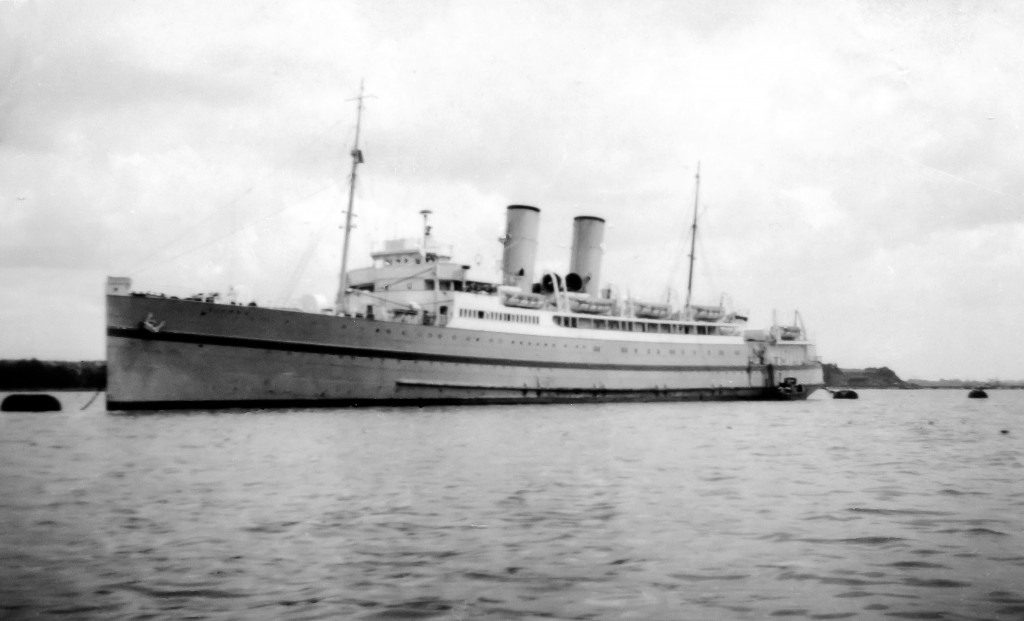

Empire Parkeston

Empire Parkeston (1946-1961) Built by Cammell Laird & Co Ltd ,Birkenhead in 1930 and originally named the “Prince Henry”. It was purchased from the Canadian Government and renamed “Empire Parkeston”. on 7th April 1946, s.s Empire Parkeston arrived at Parkeston Quay. apart from a short break at the time of the Suez crisis in 1956 and in 1957 when she sailed from Cardiff to the Hook of Holland with a Welsh Regiment on-board.

The Empire Parkeston, with her two tall funnels sizzling steam, was surrounded by a heavy mist, as troops walked the ship’s gangway for the last time. There were 771 on board, including 16 infants. After a period of lay up she left for Spezia in Italy for breaking-up on 30th January 1962.

Other vessels used. s.s. Antwerp , s.s St. Hellier. m.v. Royal Ulsterman, s.s Duke Of Rothesay , s.s Duke of York, s.s. St.Andrew, s.s Biarritz, and s.s. Manxman.

The Last of the B.A.O.R Ships

It was a grey dawn at Parkeston Quay when the troopship Empire Parkeston came in to berth. Docking arrangements were pretty much the same as they had been for the last sixteen years, but there was one notable difference – it was the last time a troopship was to tie up at Parkeston Quay on the B.A.O.R. military sea route between Harwich and Hook of Holland with service personnel and their families. After carrying 8,000,000 Servicemen and families the troopship had given way to air transport.

“A very sad occasion”

Major-General J.W.C. Williams, D.S.O., O.B.E., the Army’s Director of Movements, described the closing down of the military sea route from Harwich as “A very sad occasion for the Services”.

“Without the willing help and co-operation of everyone concerned we certainly could not have done it, “he said.

The Mayor said it was a sad occasion for Harwich too, They would be losing a lot of their goods friends from the Transit Camp at Dovercourt, but felt sure they would make many more good friends in the near future.

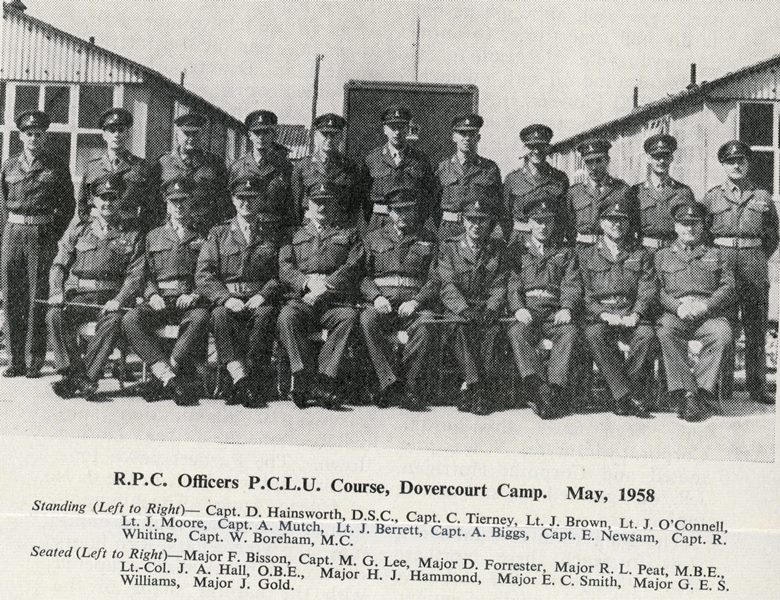

Transit Camp

A Million men have passed through Harwich going to and from there leave, The 25 acre transit camp (Number 67) which the army built for itself at Dovercourt was Designed to house up to 4,000 service Men at a time. The camp was built by the road engineers and a considerable amount of German prisoners of war, As the camp neared completion, trees and shrubs where planted in front of the camp to make it look more attractive from the outside. The camp was divided into two sections. North side of the main road would be for the Permanent staff whilst the opposite side of the road would be for British Army Overseas Rhine leave personnel.

Movement into and out of Parkeston Quay was carried out by Special Troop Trains which ran to fit in with the morning and evening sailing and arrival schedules between London (Liverpool Street Station) and the normal daily BR through train service which connected with Northern Ireland via Liverpool (Lime Street).

Up at Camp.

Transit Camp (1958)

The Transit Camp was not like most Army camps, as it was a mixture of several Regiments, and many of the personnel were throw-outs that their regiments did not want, especially some of the Infantry. The Main Gate duty consisted of recording all vehicle exits and returns, and checking that personnel leaving and returning to camp were in a fit state and dressed properly.

The accommodation which the camp offered for men returning from leave and having spent up to 12 hours in Harwich and Dovercourt pending the sailing of the ship ,rivals that of a holiday camp Magnificent lounges ,brick fireplaces, leather settees and armchairs and a huge restaurant and games room. The casualty reception station was a miniature hospital ,Men of the camp who are taken Ill while travelling to and from leave are cared for, although the most serious cases are sent to Colchester military Hospital.

National Service experience 1950 – 1952.

Down the Quay.

Down the Quay

“Two trips” said the Dutch sailor in a thick European accent, sticking two fingers up in the face of the British Army officer standing by the gangway of the troopship SS Vienna at 10pm one night on Parkeston Quay. The War Office had agreed to transport 150 sailors back to Holland, and we also had a Special Sailing in addition to the normal night ship. This was for the children of Service people, who were at Boarding school in the UK but went to Germany for the Summer Holiday with their parents. But there was no additional Quay berth available, so the “Empire Wansbeck” was tied up alongside the “Vienna” and both ships were being loaded from one gangway.

We had to count the people loading each ship, not least because the Ministry of Transport safety regulations lay down a maximum number that any ship can carry. So we had to find out from each individual going up the gangway which ship they were on, and as if this was not difficult enough these flaming Dutch sailors each had Two kitbags, which they were loading one at a time. They went up the loading gangway with one kitbag, came down the unloading gangway and then returned for a second trip. To try and avoid being double counted they were required to indicate when they boarded for the second time – which they did!

Empire Wansbeck

The troopship from the Hook of Holland arrived at Harwich at 6 am, and sailed at midnight, every other day, but there were frequent additional sailings. They conveyed all personnel for service in Germany, and were many and varied groups, including drafts (personnel being posted to or from), leave, demob, courses and also civilians on Service duty and all had to be segregated, the Officers one way, the Warrant Officers another, and the Sergeants separate from the irks. All had their particular documents and we had to sort them out, and also supervise the two or three troop trains which ran to or from Liverpool Street in connection with each arrival and departure.

On sailing days we arose at about 5am to get the truck to the Quay, where we had breakfast in the cookhouse, which was where all people coming off the boat later had theirs. The food was much better than in Camp, and when we finished at about 10 am we had another meal! In the evening we arrived at the Quay at about 7.30 pm, had our supper and hoped to be back in Camp in bed by midnight. One of the jobs I enjoyed most was going “up the line” on the 4.35 pm train from Parkeston, with a tank engine going non-stop from Manningtree to Colchester. Here I joined the Norwich to London train (with a B16 4-6-0 on 28 June, and – joy of joys – SR ‘Battle of Britain’ 34057 on 12 July) arriving at 6.45 pm, where I reported to the RTO (Railway Transport Office) and had a meal in the YMCA. Then I joined the First troop train which left at 7.40 pm running non-stop to Parkeston Quay West, which was a separate station near the troopship quay. I had quite a good time, in a First Class compartment to myself without a lot to do, and was i/c the NAAFI bar for half an hour! On arrival I did normal Quay duties until 11.30 pm.

22385278 Cpl JT Albery, RE. Copyright © 2005 Movement Control Association

Auction will decide fate of Army camp

The 38 acre site of the Army Transit Camp at Ramsey is to be sold by auction on Thursday June 11th 1970 at the London Auction Mart, by the Defence Ministry.

The existing Army huts cover 230,000 square feet. Most of the land is in Harwich borough, with a small section in Tendring rural district.

Originally the site, which was a busy army transit camp until a few years ago, was zoned for light industrial use.

The site is too costly for either Harwich or Tendring to take up, and it seems likely a private development company will be interested.

War is Over

VE- Day

On Monday May 7th at 02.41. German General Jodl signed the unconditional surrender document that formally ended war in Europe. Winston Churchill was informed of this event at 07.00. The Second World War relied on sometimes hidden contributions from the navies of the Allies, landing troops in Normandy and Sicily, bringing supplies to Russia, and helping convoys to cross the Atlantic without being destroyed by German U-Boats. During the five years of war Harwich was a front-line town, under attack from the air and with an enemy presence all too obvious if little seen out at sea.

Air raids caused considerable damage to property in the town, though fortunately civilian casualties were few, only ten lives were lost.

Winston Churchill was informed of this event at 07.00. While no public announcements had been made, large crowds gathered outside of Buckingham Palace and shouted: “We want the King”. The Home Office issued a circular (before any official announcement) instructing the nation on how they could celebrate:

Harwich Greets VE-Day with flags and fun

Although the actual announcement of VE-Day had not the spontaneity of sudden unexpected news of the end of hostilities.

There was something spontaneous about the response of the good folk of Harwich and district which, starting quietly and almost unobtrusively on Monday evening.

Throughout Monday the historic announcement was awaited hour by hour in this town which had seen to much of many wars.

Third Avenue – Street Party

By Monday evening flags were beginning to appear, at first a little self consciously, that with the radio announcement that VE-Day would be Tuesday, there was a stir throughout the town, small boys miraculously appeared with tin-cans bands, others raced round the streets with flags on their bicycles and others promptly lit bonfires.

Then came Tuesday and a steady trek for bread and meat while the shops remained open, then a stream of people to church to give thanks for their country’s deliverance from so great a peril.

Everyone Behaved

The day progressed, beer was in great demand but unfortunately for the seekers after the glass that cheers many of mine hosts, had sold or decided to celebrate VE-Day themselves and it was left to just a few of the hostelries to cope with the persistent VE-Day thirst.

By mid-afternoon, the first excitement had dies away and there was a feeling that everyone was saving their strength for the evening’s celebrations. And so, it proved. There were queues for beer, crowds of folk everywhere were in the grandest humour and it is worthy to note that the behaviour of the crowds that thronged the streets-both civilian and service- was exemplary after making allowance for the importance of the occasion.

On Dovercourt sea-front Mr. George Palmer, in keeping with his promise, placed his dance band on a lorry and it took it out into Marine-parade where hundreds of people danced and spent riotous time until darkness intervened and the coming of the black-out was a reminder that the East coast was still officially in the front line.

Last German P.O.W. Goes Home via Harwich

A Ship pulling away from the quayside, German prisoners of war lining its decks and waving farewell, the strains of “Lili Marlene” from an accordion on deck floating across the ever-widening space of water. This was the final scene of an historic moment at Parkeston Quay when the last batch of German prisoners were repatriated.

It was scene that followed a strangely dramatic farewell on the quayside, a farewell that was without special ceremony, but had within it the essence of changing times, of a kindly tolerance towards the men who were going home. Almost a bonhomie, born perhaps of the sentiment of the moment.

The party of 550 who sailed from Harwich brought to a total of 220,000 the German prisoners who have been repatriated through Harwich of the past eleven months.

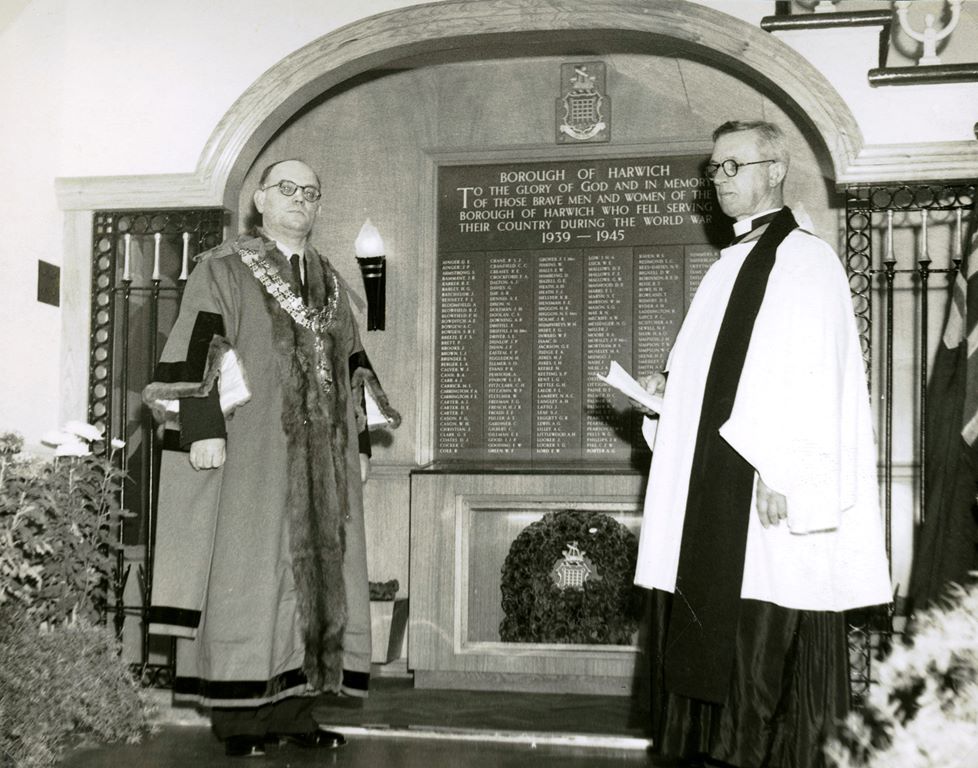

War Memorial Dedication

30th November 1952 saw the dedication of the War Memorial, within the foyer of the Town Hall, to the residents of the borough who gave their lives during the 1939-1945 war.

War Memorial dedication

The cost of erecting the War Memorial was defrayed from the balance of the Harwich War Memorial and Community Centre Fund and takes the form of a small open chapel and the centre motif of the bronze plaques show the names of the 218 men and women who gave their lives in World War II 1939-1945.

At the Dedication on the two flank walls of the chapel the following flags were placed folded in oak frames and covered with plate glass:

- Union Jack

- White Ensign of the Royal Navy

- Royal Air Force Flag

- Red Ensign of the Merchant Navy.

The two oak flower boxes which can be seen in the photograph contained 218 poppies, representing one for each name inscribed on the memorial.

However, over 70,000 servicemen and more than 1,500 ships had been lost during the two World Wars, with these figures showing that while it may be ‘a sweet and honourable thing to die for your country’, it can also be a costly proposition.

Photo Gallery

Click “play” to start the gallery slide show. The gallery will scroll through the pictures automatically.

We hope you will enjoy browsing these wonderful photographs of Harwich at War.

We are adding more information to this site on a regular basis, if you wish to submit any photos or provide any information, please use the contact page at the bottom of the screen.

Acknowledgements:

- The Harwich Society, Harwich and Dovercourt in Old Picture Postcards, BBC WW2 People’s War,

- Rik Alewijnse, Julian Foynes.